Kwanzaa

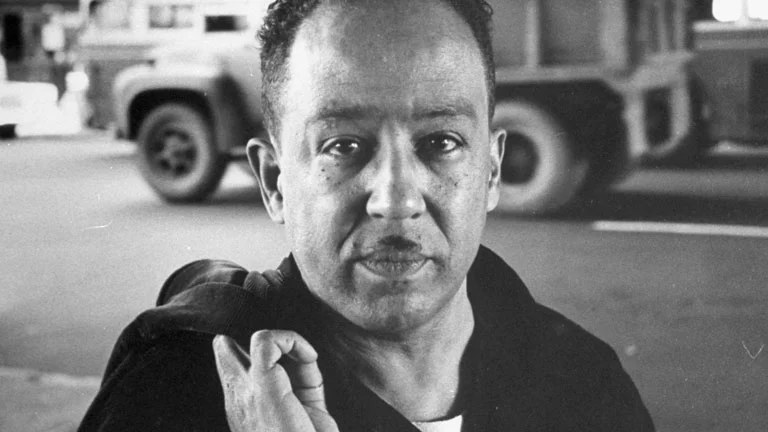

As a reaction to the 1965 Watts riots in California, visionary Maulana Karenga created a holiday for Black Americans. Karenga's ideal holiday carved out spaces for free expression while adhering to the seven principles. Karenga wanted to provide a venue for Black Americans to support Black institutions, values, and traditions.

In 1966, Karenga used the creation of Kwanzaa as a means of connecting Black communities across the U.S. with their African roots. Kwanzaa was created to keep the community unified and inspired despite marginalization by the U.S.'s dominant, oppressive white culture.

The name Kwanzaa is derived from a Swahili phrase, "matunda ya kwanza", meaning first fruits.

Every year Kwanzaa falls on the seven days between Christmas and New Years Day. The break from the traditional Swahili with the second letter "A" at the end of Kwanzaa was added to highlight the seven days of celebration:

Day 1: Umoja (Unity)

Day 2: Kujichagulia (self-determination)

Day 3: Ujima (Collective work and responsibility)

Day 4: Ujamaa (cooperative economics)

Day 5: Nia (purpose)

Day 6: Kuumba (creativity)

Day 7: Imani (faith)

Seven Core symbols of Kwanzaa:

1. Mazao: Crops

2. Mkeka: Place Mat

3. Muhindi: Ear of Corn

4. Mishumaa Saba: The Seven Candles

5. Kinara: The Candleholder

6. Kikombe Cha Umoja: The Unity Cup

7. Zawadi: Gifts

Similar to the Jewish tradition of lighting candles on the menora, in Kwanzaa, families gather to light the candles on the kinara, during communal feasts.

Karenga did not have to work hard to spread the word. Once college students learned of this new Black celebration, news spread like wildfire and families began incorporating Kwanzaa celebrations into their other annual celebratory traditions. However, despite Kwanzaa's growing popularity, many Black Christians were hesitant to partake in Kwanzaa celebrations, as they did not want to replace Christmas traditions. But as popularity continued to rise throughout the 60s, Black churches began supporting Kwanzaa celebrations and this strengthened its position in the Black community.

Though the Civil Rights Act did not eradicate societal ills connected to racism, it did dramatically reduce race-based discrimination in the workplace. The legal termination of this practice resulted in exponential earning growth in Black wealth. This explains the reason for Kwanzaa's increased popularity in the 1970s – as Black wealth rose, many families were in a position to move away from the cities into white suburban neighborhoods. With Black families feeling isolated, Kwanzaa provided a psychological reprieve from their mostly white communities. Despite Black people comprising thirteen percent of the U.S. population, only three percent of Americans still celebrate the winter holiday.